With my custom MCP4922 PCB assembled, it is time to test it. Soldering is good and fine fun, but the whole point is to get something that actually works!

Connecting to Arduino: My plan is to connect it to an Arduino and to have it generate a variety of DC voltages. Unfortunately, it was at this point that I realized I had no female wires to mate to the male headers that I put on my board. Doh! So, I had to use alligator clips which are a real pain to work with. As you can see in the picture above, it is difficult to keep them from touching each other and shorting everything out.

Jumper Some Pins: Another hiccup is that, as I was hooking it all up to to the Arduino, I realized that I designed my PCB to be overly-general. Specifically, I when I designed the board, I brought out two of the MCP4922 pins (*SHDN and *LDAC) to the header when I really didn't need to. For the way that I use this chip, I just need *LDAC tied LOW and *SHDN tied HIGH. Doing this with alligator clips is annoying, so I just soldered short jumper wires on the bottom of the board to connect these pins to GND and VDD. This simplified my setup nice.

Arduino Software: With the hardware all hooked up, I wrote a little Arduino program to drive the DAC. You can get the code here. The code outputs two different voltages on the A and B outputs of the DAC to prove that they work. Output A steps from 0.0V up to 5.0V in one volt increments. Output B does the opposite -- it steps from 5.0V down to 0.0V in one volt increments.

Victory: Starting up the program, it automatically stepped through its commands for the different voltages. I measured the voltages with my digital multi-meter (DMM) to confirm that I was getting the correct output. As you can see in the pictures below, Output A of the DAC does a pretty good job of hitting the voltages that I wanted. My first PCB works! Victory!

Exploring the Error: Because I'm a nerdy guy, I couldn't leave it there. I couldn't just enjoy my victory in peace. No. I had to look at the results in more detail. Specifically, I was troubled by the fact that the values reported by the DMM were not quite as close to my desired values as I hoped.

Should be Better?: I hoped to see exact round numbers spanning 0.0 up to 5.0V. As you can see in the pictures above, my DMM is reporting values that are off by 1-15 mV. That seems like a lot of error for a 12-bit DAC. I mean, on the surface, one might expect an accuracy from the DAC of approximately 1 least significant bit (LSB). One can compute the magnitude of 1 LSB by scaling from the "full scale" voltage of the device. Since I'm running it at 5.0V, 1 LSB is (5.0 V / 2^12 bits) = (5.0 / 4096) = 1.2 mV. This is quite a bit smaller than the 15 mV of error that I'm seeing in some cases. My gut feeling is that I should be doing better. So, I started to dig into the details...

Error in Full Scale: First, note that my DMM shows that the "5.0V" case is actually indicating 5.015V. This suggests that my "full scale" is actually bigger than 5.0V -- that it is actualy 5.015 V. In my setup, "full scale" is set by the voltage of the power being delivered to the PCB, which is coming from the Arduino. The Arduino (Uno) is nominally outputs 5.0V, but it is not a precision voltage reference. For example, the on-board regulator is only good to +/-50 mV and others have also seen their Arduino "5.0V" be off by 12-14 mV. So I do not find it surprising that full scale voltage could be running 15 mV higher than expected. If you want a precise "full scale", you probably have to build/buy a precision voltage reference instead of using the Arduino's 5V pin.

New Expected Values: What does the 5.015V "full scale" value mean for my expectations for the DAC output? Well, since all of the DAC's output values are scaled from this full scale value, the output values that I should actually expect to see are 0.000V, 1.003V, 2.006V, 3.009V, 4.012V, and 5.015V. These values are closer to the ones that I actually saw, which is good. My measured values are now only off by 0-6 mV (the worst error is for the 2 V reading). Still, 6 mV is larger than the 1.2 mV error that I might expect based on 1 LSB, so I'm still not satisfied.

DAC Error from Datasheet: My next idea is that maybe my expectation of 1 LSB accuracy is wrong. Digging into the datasheet for the MCP4922, I see in the big table on page 5 under "DC Accuracy" that the INL error can be +/- 4 LSB (!). If 1 LSB is 1.2 mV, then a 4 LSB error would correspond to 4.8 mV. That's a lot closer to the 6 mV error that I seem to have...but it's still doesn't account for all of it.

Error in DMM: My next idea is that maybe the error isn't all with the DAC. Maybe some of the error is in my DMM. Looking at the user manual for my Extech EX530 digital multi-meter, it states that the device has an accuracy of "+/- (0.06% reading + 2 digits)". Let's compute what that means for my problematic 2V reading. First, at 2V, 0.06% is 1.2 mV. Second, "2 digits" means 2x the value of the smallest digit on the display. For the 2V reading, the smallest digit is 0.1 mV, so "2 digits" is an error of 0.2 mV. As a result, the total error for my DMM could be +/- 1.4 mV.

Total Error: Combining this 1.4 mV of possible error for the DMM with the 4.8 mV of possible error for the DAC, I get a total error of up to 6 mV. This happens to be the same amount of error that I actually saw. While that's good (I guess), it is also unsatisfying because it requires all of my errors to be at their maximum. For now, I'm going to accept that. But, moving forward, I'm going to keep an eye on how closely my DAC's values are to my desired values.

Thanks for reading!

[Note: The comment section of this post is closed due to too much spam from PCB services.]

Thursday, August 21, 2014

Wednesday, August 20, 2014

Assembling my MCP4922 DAC Breakout

One of my most popular posts was this one on making a simple PCB for the MCP4922 DAC. I'm so glad that people were interested in this! After a long delay, I have finally decided that it is time to assemble the PCB. Let's do it!

This post will be mostly pictures showing how I soldered in the parts. My technique is pretty poor, so don't take this post as guidance on how you *should* do it. Instead, take this post as comfort that you can be bad at soldering and still get things to work just fine.

First, I got my MCP4922 chip from Digikey. Currently, $3.14 each, when bought singly.

I inserted the chip into the PCB. Fits just fine!

I flipped over the PCB to work on the legs of the chip.

I soldered each of the legs:

With all of the legs are soldered, the picture below shows that the joints in the front row are pretty nice, but that the joints in the back row have too much solder. Oh well. I'll try to do better next time.

Upon close inspection, I feel that the legs stick out too far. So, I trim them with my wire snippers. I wish I had better snippers. These don't snip very well. Better ones might let me snip flush against the PCB.

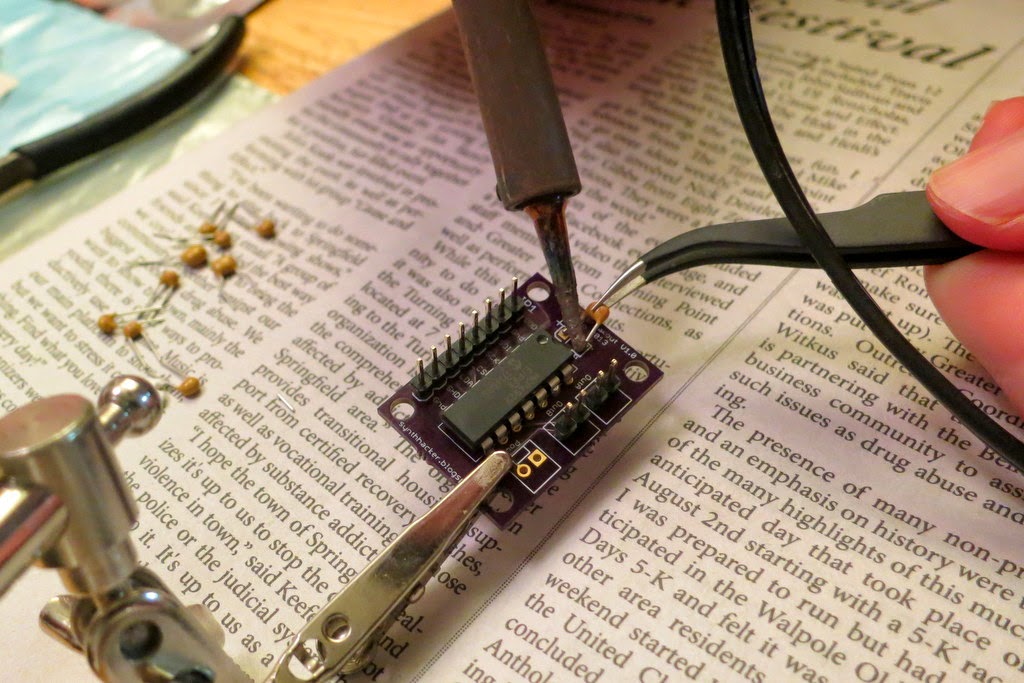

Once all the pin headers are in place, I need to solder in the two caps (10 uF and 0.1 uF) to decouple the power supply. In the design of the PCB, I was bold and made both of them be surface mounted parts. I have barely worked with surface mount components, so I don't really know what I'm doing. In the picture below, you see me starting by tinning the pads. I don't know if this is the right thing to do, but here I go...

After tinning, I try soldering on the surface-mount capacitor. I'm not sure what the best technique is. I had to try it several times until I was able to get both ends of the cap to be decently connected. I am glad that I bought some nice tweezers, though.

So that was the cap on the bottom of the board. The other cap is on the top of the board. Unfortunately, I didn't have another surface mount cap of the right value, so I used a small through-hole cap instead. I snipped the legs really short and tacked it on with solder. This is not recommended, but it got the job done.

And, finally, I'm finished! (I left one connector unpopulated because that's just an extra connection for power, which I don't need).

This post will be mostly pictures showing how I soldered in the parts. My technique is pretty poor, so don't take this post as guidance on how you *should* do it. Instead, take this post as comfort that you can be bad at soldering and still get things to work just fine.

First, I got my MCP4922 chip from Digikey. Currently, $3.14 each, when bought singly.

I inserted the chip into the PCB. Fits just fine!

I flipped over the PCB to work on the legs of the chip.

I soldered each of the legs:

With all of the legs are soldered, the picture below shows that the joints in the front row are pretty nice, but that the joints in the back row have too much solder. Oh well. I'll try to do better next time.

Upon close inspection, I feel that the legs stick out too far. So, I trim them with my wire snippers. I wish I had better snippers. These don't snip very well. Better ones might let me snip flush against the PCB.

The chip is now fully soldered in place. The next step is to add the connectors around the edge of the board. I could have used male pin headers or female. I only had male headers on hand, so that's what I used. As you can see below, I used a blank proto-board to hold the pins in place so that they poke up straight through my PCB. Then I solder them in place.

Once all the pin headers are in place, I need to solder in the two caps (10 uF and 0.1 uF) to decouple the power supply. In the design of the PCB, I was bold and made both of them be surface mounted parts. I have barely worked with surface mount components, so I don't really know what I'm doing. In the picture below, you see me starting by tinning the pads. I don't know if this is the right thing to do, but here I go...

After tinning, I try soldering on the surface-mount capacitor. I'm not sure what the best technique is. I had to try it several times until I was able to get both ends of the cap to be decently connected. I am glad that I bought some nice tweezers, though.

So that was the cap on the bottom of the board. The other cap is on the top of the board. Unfortunately, I didn't have another surface mount cap of the right value, so I used a small through-hole cap instead. I snipped the legs really short and tacked it on with solder. This is not recommended, but it got the job done.

Thursday, March 13, 2014

Polysix - Sharing my Arduino Code

As many of you know, I made some pretty substantial modifications to my Korg Polysix. One of the biggest changes was to replace the keybed to enable aftertouch. To make this happen, I had to replace the Polysix's Key Assigner with an Arduino. It was a lot of work, but once I made the core hardware modifications, I found that I was able to add lots of features to the Polysix, such as: aftertouch and portamento, more interesting detuning for unison mode, a poly-unison mode, a Moog-like single-trigger mode, and a sustain pedal. All of these modifications were effected through software changes on the Arduino.

Since I have made those modifications, I have had some people ask if I could share the software. At first I declined, because I was embarrassed of the poor quality of the code. I also didn't really know how to share it. Then, I learned how to use GitHub. So, I at least know how to share my code now. All I have to do is get over my embarrassment. Well, here we go...

If you want to look at some nasty code for how to replace the Polysix Key Assigner using an Arduino, you can find my GitHub repository at: https://github.com/chipaudette/ArduinoPolySix.

Yes, my code is tortured and very difficult to follow. But, that's what happens when you're just learning how to do this stuff. Sorry. If I were to re-write it from scratch it would look a lot different...but this is what I have now. Maybe you'll find something useful.

Thanks for reading!

Since I have made those modifications, I have had some people ask if I could share the software. At first I declined, because I was embarrassed of the poor quality of the code. I also didn't really know how to share it. Then, I learned how to use GitHub. So, I at least know how to share my code now. All I have to do is get over my embarrassment. Well, here we go...

If you want to look at some nasty code for how to replace the Polysix Key Assigner using an Arduino, you can find my GitHub repository at: https://github.com/chipaudette/ArduinoPolySix.

Yes, my code is tortured and very difficult to follow. But, that's what happens when you're just learning how to do this stuff. Sorry. If I were to re-write it from scratch it would look a lot different...but this is what I have now. Maybe you'll find something useful.

Thanks for reading!

Labels:

Aftertouch,

Arduino,

Detune,

GitHub,

Keybed,

Korg,

Mod,

Modification,

Pedal,

Poly-Unison,

Polysix,

Portamento

Saturday, March 8, 2014

Portastudio - Voltage Control of Speed

After my experiments with live looping using my Portastudio 424, I keep thinking about what interesting modifications I can do to push the Portastudio into unexpected places as a performance instrument. One idea was to expand the user control over the playback speed of the tape so that I could arbitrarily vary the pitch of the recorded audio. Sure, the 424 gives some control over the tape speed, but it does not allow you to smoothly span a wide range. So, I started looking into how I could modify the 424 to give me what I wanted. Ideally, if I truly get aribrary control over the tape speed, I could turn my Portastudio into a monophonic Mellotron, which could be kinda cool! Here's the story of what I've discovered....

Built-In Pitch Controls: As shown in the picture above, the Portastudio 424 comes with two user controls over tape speed. First, there is a 3 position switch that sets the gross tape speed to either "slow" (15/16 inch per second), "normal" (standard 1 7/8 inch/sec), and "high" (3 3/4 inch/sec). Assuming that it is usually set in the "normal" position, this switch lets you either drop the pitch by an octave or raise the pitch by an octave. If you want finer control, you can use the pitch adjust knob. Unfortunately, this only allows you to lower or raise the pitch by about 2 semitones. So, there is a big gap between the gross tape speed switch and the fine pitch adjust knob. I would like to modify the Portastudio to allow smooth changes between any pitch. Let the hacking begin!

The Cassette and Motor Assembly: My first step was to open up the Portastudio to see how the cassette playback assembly is put together. As you can see above, opening the Portastudio reveals a big circuit board that surrounds an assembly that holds the cassette, motors, and other mechanical bits. Looking in detail at the cassette and motor assembly (picture below), you can clearly see the thin metal capstan and its corresponding pinch roller. The capstan (and its roller) are what pull the tape over the playback head. It is the capstan that controls the speed of the playback. Controlling the speed of the capstan is the key to controlling the speed of the tape playback.

Capstan Motor: Removing the cassette and motor assembly from the Portastudio, the picture below shows its underside. It is a very complicated mechanical assembly with multiple motors, gears, belts, and circuit boards. Staying focused on just the elements associated with the capstan, one can see a big flywheel that is directly attached to the backside of the capstan itself. The flywheel is driven from a belt attached to a the capstan motor. The capstan motor is attached to a circuit board via four electrical terminals. This must be how the speed of the capstan is controlled.

Four-Wire Connection: Frankly, I was surprised to see that the motor had four wires to control it. Not knowing anything about cassette players and capstan motors, I expected to find a basic DC motor with just two terminals. I expected that the speed would be controlled by changing the DC voltage of the positive terminate or by using PWM of the the positive voltage applied to the motor. Apparently, that's not the case. How is this motor controlled?

Looking at the Schematic: When it isn't clear how something works, it is usually best to consult the schematic. Sadly, I don't have a schematic for the Portastudio 424. Even scouring the internet (and visiting some unsavory web forums) did not yield the schematic. The closest that I got was on eBay where someone was selling a paper copy of the Service Manual (which includes the schematics) for the Portastudio 464. Since the 464 and the 424 were out a similar times, my hope was that the schematics would be close enough to enable my hacks. So, I ordered it. When I arrived, I found that the capstan motor and speed controls (in the 464) were wired as shown below. It clearly shows the four wire connection -- two connections for power (12V and ground) and two connections ("B" and "A") that loop out through the user controls. These must control the speed. But why are the connections configured as a loop, instead of just injecting a commanding voltage signal from the outside?

Finding the Command Terminal: Using my digital multi-meter (DMM) with the Portastudio turned on, I quickly determined that on my 424, Pin #4 is ground. This is in contrast to the 464 schematic, which showed ground as Pin #1. Regardless, moving forward, I put in a cassette and pressed play. Then, using Pin #4 as a reference, I measured the voltage at the other three terminals for different speed settings. The values are shown in the graph above. As can be seen, the voltage at Pin #1 drops as the speed increases. The voltage at the other pins stays the same (basically). So, I think that this confirms that Pin #1 is the terminal for the speed command signal, because it is the only one that changes with speed. It appears likely that Pin #3 is the power supply for the motor, because it is the highest voltage signal and stays firm at +12V. Therefore, through process of elimination, Pin #2 must be the terminal associated with the speed sensing.

Command Voltage: According to the 464 schematic, the speed command voltage is set by drawing current out of the speed sense pin (Pin #2 in the 424), and altering the voltage delivered to the command pin (Pin #1 in the 424). Therefore, we would expect the voltage at Pin #1 to be lower (ie, negative) relative to Pin #2. The blue line in the graph above shows voltage measurements that I made that confirm this expectation. As you can see, the slowest speed exhibits a voltage at Pin 1 that is about -0.5V relative to Pin #2. As the speed is increased. the voltage at Pin 1 eventually reaches about -3.5V relative to Pin 2. Again, this is the relative voltage...the absolute voltage (well, relative to ground) was shown in an earlier graph and is running between +8.5V and +11.5V.

Pitch vs Speed: So now that we have a good handle on how the Portastudio changes the command voltage based on the user settings for the tape speed, there is still the question of how much the speed of the tape actually changes. Since tape speed directly affects the pitch of the audio that has been recorded to the tape, I've decided to quantify the change in tape speed by recording a tone onto the tape (at "Normal" speed) and then measuring the frequency of the tone as I change the speed. The results of this experiment are shown as the red line in the graph above. As expected, higher tape speed results in higher frequency. Plotting frequency directly against the capstan command voltage, we get the relationship shown below. Nice and linear. Excellent.

Creating the Command Voltage: OK, now we're getting serious. If I really want to make a mellotron out of my Portastudio, I have to generate the precise command voltage in order to achieve the pitch that I want. The "command voltage" is is the voltage at Pin #1 relative to Pin #2, both of which are riding well above ground. Assuming that I'm creating my command voltage from a 0-5V sounce (such as from an Arduino or something), I need a circuit that will both boost the voltage up to the correct DC level and to adjust the voltage based on whatever is happening on Pin #2. The circuit shown below should do exactly that.

|

| Built-In Tape Speed / Pitch Controls on my Portastudio 424 |

|

| Opening the Portastudio, you can see the cassette and motor assembly in the upper right. |

|

| Zooming in on the cassette and motor assembly, you can see the capstan and its mating pinch roller. This is what controls the tape speed. |

|

| Looking at the underside of the cassette and motor assembly. You can see the capstan flywheel, which is belt-driven by the capstan motor, which I'm probing using my clip leads. |

|

| Rotating the cassette and motor assembly again. Here you can see that the capstan motor terminals are labeled 1-4. |

|

| Assuming Motor Pin 4 is Ground, Here are the Voltages that I Measured at Different Tape Speeds. Pin 1 Appears to Control the Tape Speed. |

Finding the Command Terminal: Using my digital multi-meter (DMM) with the Portastudio turned on, I quickly determined that on my 424, Pin #4 is ground. This is in contrast to the 464 schematic, which showed ground as Pin #1. Regardless, moving forward, I put in a cassette and pressed play. Then, using Pin #4 as a reference, I measured the voltage at the other three terminals for different speed settings. The values are shown in the graph above. As can be seen, the voltage at Pin #1 drops as the speed increases. The voltage at the other pins stays the same (basically). So, I think that this confirms that Pin #1 is the terminal for the speed command signal, because it is the only one that changes with speed. It appears likely that Pin #3 is the power supply for the motor, because it is the highest voltage signal and stays firm at +12V. Therefore, through process of elimination, Pin #2 must be the terminal associated with the speed sensing.

|

| After recording a ~65 Hz tone at the normal tape speed, I see that there is a nice inverse relationship between the motor control voltage and the resulting pitch. |

Pitch vs Speed: So now that we have a good handle on how the Portastudio changes the command voltage based on the user settings for the tape speed, there is still the question of how much the speed of the tape actually changes. Since tape speed directly affects the pitch of the audio that has been recorded to the tape, I've decided to quantify the change in tape speed by recording a tone onto the tape (at "Normal" speed) and then measuring the frequency of the tone as I change the speed. The results of this experiment are shown as the red line in the graph above. As expected, higher tape speed results in higher frequency. Plotting frequency directly against the capstan command voltage, we get the relationship shown below. Nice and linear. Excellent.

|

| The relationship between control voltage and pitch is nice and linear. |

Creating the Command Voltage: OK, now we're getting serious. If I really want to make a mellotron out of my Portastudio, I have to generate the precise command voltage in order to achieve the pitch that I want. The "command voltage" is is the voltage at Pin #1 relative to Pin #2, both of which are riding well above ground. Assuming that I'm creating my command voltage from a 0-5V sounce (such as from an Arduino or something), I need a circuit that will both boost the voltage up to the correct DC level and to adjust the voltage based on whatever is happening on Pin #2. The circuit shown below should do exactly that.

|

| Notional Op-Amp Circuit Configuration to Generate the Correct Capstan Command Voltage (Pin #1) Given a 0-5V Input Voltage. [Revised, Mar 9, 2014] |

Picking the Right Input Voltage: While the circuit above should achieve my goals, it is an inverting amplifier with respect to the input voltage that I'll be injecting. This means that an upward-going input signal results in a downward-going output signal. As a result, the relationship shown earlier in the frequency-vs-voltage plot shown earlier is inverted. To account for the inversion, I made the graph below. Also, because I actually care about the perceived pitch of the tone (the note on the scale), not the actual frequency of the tone, I converted "frequency" axis into "pitch". With this new graph, I can choose how many semitones of pitch shifting I want (say, shift up an octave, which is 12 semitones) and then I can simply read off the voltage that I need to send to my op-amp circuit (in this case, +12 semitones requires a voltage of +3.25V. Easy!

Next Steps: With all of this analysis, I think that I have figured out how to control the tape speed of the Portastudio 424 to get the pitch shifting that I want. Now I have to go and try it out. It's time to smell the solder!

UPDATE, Mar 9, 2014: I tried building the original op-amp circuit that I showed. It did not have the correct input-output relationship at all. The problem was that I did not include any of the resistors (R3 and R4) that are now shown on the non-inverting input. Ooops! Adding R3 and R4, the input-output relationship is now correct.

|

| If I want to achieve a certain pitch, here is the relationship that determines the control voltage that I need to generate. |

Next Steps: With all of this analysis, I think that I have figured out how to control the tape speed of the Portastudio 424 to get the pitch shifting that I want. Now I have to go and try it out. It's time to smell the solder!

UPDATE, Mar 9, 2014: I tried building the original op-amp circuit that I showed. It did not have the correct input-output relationship at all. The problem was that I did not include any of the resistors (R3 and R4) that are now shown on the non-inverting input. Ooops! Adding R3 and R4, the input-output relationship is now correct.

Tuesday, February 18, 2014

Portastudio - Live Looping

I'm continuing with my goal of turning my Tascam Portastudio 424 into a live performance instrument. A key step was to take a regular cassette tape and to turn it into a continuously looping tape. At normal speed on the Portastudio, my loop tape gives about a 5 second loop. In trying to use the Portastudio as a live instrument, I've been learning how to record to the loop tape and to play back from the loop tape all in real time. As with any instrument, it takes time and practice to figure out the interesting techniques and effects that the instrument enables. Below is a demo of what I've figured out so far.

Recording to Tape: To record audio to tape, the Portastudio allows several different methods. Which method you choose is driven by your needs. Because I want to use it as a live looper, I'm hoping to find a method that causes the Portastudio to play back the recorded audio as a loop as soon as I finish recording recording it. Ideally, this will happen with no break in the action. While this is trivially easy on a digital looper like the Kaossilator, it is a little trickier on a tape-based machine, since live looping is not what this kind of tape-based machine is designed to do.

Punch-In/Punch-Out: Luckily, the Portastudio is designed to allow you to easily toggle between record and play modes without stopping the tape. This is the "punch-in" / "punch-out" practice that allows one to, say, redo a guitar solo without affecting the guitar that was recorded just before and just after the solo. When we use our loop tape instead of a normal tape, this means that we can hear our loops, then "punch-in" to overwrite all or part of the loop, and then "punch-out" to let the loop resume playing. You start the process by simply hitting "play" on the Portastudio. To "punch-in", you hit the Record button (or press the "punch-in/punch-out" footswitch, like I do in the video). To "punch-out", you hit the Play button again (or press the footswitch again). At no point do you hit Stop...it just keeps going continuously.

Input Setup: The Portastudio can configure its inputs a number of ways. To get the Portastudio to playback your newly-recorded audio as soon as you punch-out, you need to use the configuration shown in the pics below. The key is that you setup your target track (in this case, Track 1) to record NOT what is directly plugged into Track 1, but instead to record whatever is on the master bus. You do this by setting the Track 1 Input to "Mic/Line > L". Here, it'll record whatever is on the left channel of the master bus. Critically, when the Portastudio is not in record mode, this setting also causes the Portastudio to simply playback whatever is on that track. This is how you get it to play back the audio (without any further action) as soon as you punch-out.

Punch-In/Punch-Out: Luckily, the Portastudio is designed to allow you to easily toggle between record and play modes without stopping the tape. This is the "punch-in" / "punch-out" practice that allows one to, say, redo a guitar solo without affecting the guitar that was recorded just before and just after the solo. When we use our loop tape instead of a normal tape, this means that we can hear our loops, then "punch-in" to overwrite all or part of the loop, and then "punch-out" to let the loop resume playing. You start the process by simply hitting "play" on the Portastudio. To "punch-in", you hit the Record button (or press the "punch-in/punch-out" footswitch, like I do in the video). To "punch-out", you hit the Play button again (or press the footswitch again). At no point do you hit Stop...it just keeps going continuously.

Input Setup: The Portastudio can configure its inputs a number of ways. To get the Portastudio to playback your newly-recorded audio as soon as you punch-out, you need to use the configuration shown in the pics below. The key is that you setup your target track (in this case, Track 1) to record NOT what is directly plugged into Track 1, but instead to record whatever is on the master bus. You do this by setting the Track 1 Input to "Mic/Line > L". Here, it'll record whatever is on the left channel of the master bus. Critically, when the Portastudio is not in record mode, this setting also causes the Portastudio to simply playback whatever is on that track. This is how you get it to play back the audio (without any further action) as soon as you punch-out.

|

| Overall Configuration To Record to Track 1 and then Get Instant Playback of Loops After Punching-Out. |

Cue Bus: Once you get one track recorded, you'll want to listen to that track while you record the next tracks. In normal operation, you'd just have those tracks play back their audio on the master bus. But, once you configure Track 2 to record like we did for Track 1, it'll record everything on the master bus...including your already recorded audio on Track 1. Bad. So, what you do is silence the playback of Track 1 on the main bus (by pulling down the volume slider) and instead play Track 1 on the Cue Bus. As long as your headphone (ie, the "Monitor" buttons) are set to Left+Right+Cue, you'll hear all of the audio nicely. So, after recording each track to tape, silence it on the main bus and bring it up on the Cue Bus. Now you're ready for the next Track!

|

| Settings for the Cue Bus so that I hear all tracks via the Cue Bus, except for Track 1, which was already set for the Master Bus. |

Live Effects Loop: Now we get tricky. As you saw in the video, after I recorded four tracks onto my loop tape, I hooked up the Monotron Delay to be an effects box for the already-recorded audio. I was able to selectively and dynamically send audio from different tracks to the Monotron for filtering and echo effects. I did this by re-using the Cue Bus. Once my tracks were all recorded, I did the opposite of what I described above -- I moved all of the tracks off the Cue Bus and put them all back onto the Master Bus. I then set my headphones (ie, the "Monitor" buttons) to listen only to the Master Bus. That way, I could selectively send channels to the Cue Bus (via the Tape Cue knobs shown above) without hearing it. Interestingly, the mixed audio on the Cue Bus is available via the "Effects" jack on the back of the Portastudio. Secretely, this output jack is a stereo output. One channel is the Effects Bus (which, despite its name, is not helpful in this scenario) while the other channel is the Cue Bus. So, I plug Cue Bus into the Aux In of my Monotron Delay. I then leave the Monotron's output plugged into the Master Bus so that I can hear the echos. Instant live effects!

So this is the best setup that I have found for doing live looping with the Portastudio. The key with this method is that the tape never stops, so your groove can just keep on going.

So this is the best setup that I have found for doing live looping with the Portastudio. The key with this method is that the tape never stops, so your groove can just keep on going.

Labels:

Cassette,

Kaossilator,

Korg,

Monotron,

Portastudio,

Tape Loop,

Video

Sunday, February 16, 2014

Portastudio - Defeating the Erase Head

As discussed in my last post, I've been exploring the use of tape loops in my Tascam Portastudio 424. I'm trying to turn the old Portastudio into a live performance instrument, especially one the allows me to exploit the imperfections in audio cassette technology. As I started to do live looping, however, I discovered that any loop that I recorded would have a gap in the audio. I found that, to eliminate this gap, I needed to defeat the erase head on the Portastudio. Today's post describes that story. To get started, below are some audio demos with the erase head enabled (like normal) and with it defeated (which gets rid of the gap!). There's a third track in the playlist that demonstrates how, with the erase head defeated, you can now layer multiple sounds on a single track of tape. Fun!

The Portastudio 4-Track Cassette Recorder: Below is a photo of the outside and of the inside of my Portastudio cassette recorder. Since I have no schematic for my Portastudio (does anyone have one that they can send to me?), I'm forced to figure things out by physical examination. So, like a doctor poking and prodding, let's begin...

Erase Head vs Record Head: Since I assumed that my problem with the gap in my recorded loops was due to the erase head, I began my examination with finding the erase head. As you can see in the picture below, it is nicely labeled. You can also see that it is indeed physically separated from the play/record head (by about an inch). When recording (or playing), the tape passes over the erase head to be cleared prior to passing over the record head to receive the new audio. As a result, there is always a one-inch section of the tape that will contain no audio at all. This is the gap that I have been hearing in my loops.

Follow the Wiring: To figure out how I can defeat the erasing process, I looked at the wires that are connected to the erase head to see where they go. As you can see in the picture above, the wires from the erase head are mostly black, whereas the wires from the play/rec head are gray. Following those wires back to the main circuit board, I found that the gray wires (the play/rec wires) go back to the four individual circuits on the main PCB. The erase wires, by contrast, all come back to a single 8-wire connector on the main PCB.

Unplug the Connector: The easiest way to defeat the erase head is, perhaps, simply to unplug it. So, that's what I tried.

What are the "Erase" Signals: Because I was interested, I hooked up my oscilloscope to the pins on the connector that I just unplugged. I wanted to see what signals where being sent to the erase head. The pictures below show what I found. The connector has 8 pins, and each pair seem to give similar signals (I'd assume that each pair represents a single channel on the 4-track tape). For each pair of pins, one pin showed an 87 kHz signal with an amplitude of ~134 mV RMS. The other pin showed no signal, so it might be ground. I'm assuming that the 87 kHz is the bias signal used by cassette systems as the carrier for real audio signal that is amplitude modulated on that carrier. Since this is the erase head, there should be no audio, so it should just be the 87 kHz signal. This appears to be what I see.

Trying it Out: So, with the erase head disconnected from the main PCB, I tried recording some audio. As a sound source, I used my Korg Monotron with its funny little ribbon controller. As you heard in the demo tracks tat the top, when I defeat the erase head (by disconnecting it from the main PCB), I successfully eliminate the gap from my looped audio. Fantastic.

Visualizing the Results: In addition to listening to the demos, you can see the tracks visually in the spectrograms below. All of the tracks show recordings from the loop tape of the Monotron. The top figure shows a single loop of audio excerpted from a recording when the erase head was connected and active. Note the half-second gap at the end of the loop, which corresponds to that one-inch piece of tape between the erase head and the record head. The middle plot shows the result after I unplug the erase head. Note that the gaps is gone...the loop is continuous. This is what I hoping for.

Layering Audio in One Track: Another important effect of defeating the erase head is that nothing clears the track between recordings. So, when you go to record audio onto a track, it becomes layered on top of the audio that was already there. An example of this sound-on-sound recording is given in the third audio demo (and in the third spectrogram above). Here, I first recorded the basic warbling tone from the Monotron as already seen in my other examples. This is "Layer A". Then, onto the same track, I recorded the Monotron with wilder variations in pitch. This is "Layer B". As is clear in the audio demo and in the spectrogram, both layers are clearly there. Note that this is not a mixture that has been done electronically (ie, read the previous track, mix it with the in-coming new audio, then record the mixed audio onto a fresh track). No, this mixture is being done on the tape itself. As far as I know this is very uncommon.

Imperfect Layering: I believe that one reason why it is uncommon to mix audio onto tape this way is because the layering is far from perfect sounding. Note that as "Layer B" dives from high-pitch to low-pitch (see the blue arrow), it seems to suppress a lot of the "Layer A" sound. It's not until the pitch of "Layer B" raises a bit that the tone from "Layer A" sounds strong again. To most people, this interaction between the two layers of audio would be an undesirable trait. But, not for me...I'm purposely looking for unusual side-effects of using tape. So, to me, this kind of weird artifact is gold!

Moving Forward: Right now, to enable or disable the erase head, I need to use that connector inside of the Portastudio. It would be great if I could put it on a switch so that it was accessible on the outside of the Portastudio. Unfortunately, switching 8 signals (there are 8 pins on that connector) is a hassle. I'm hoping that, with more exploration, I can confirm that I only need to switch 4 of the signals (maybe just the grounds need to be connected or disconnected). If so, this will be a great behavior to have switchable.

Have any of you hacked your cassette recorders? What have you done?

The Portastudio 4-Track Cassette Recorder: Below is a photo of the outside and of the inside of my Portastudio cassette recorder. Since I have no schematic for my Portastudio (does anyone have one that they can send to me?), I'm forced to figure things out by physical examination. So, like a doctor poking and prodding, let's begin...

|

| My Tascam Portastudio 424, Outside and Inside |

Erase Head vs Record Head: Since I assumed that my problem with the gap in my recorded loops was due to the erase head, I began my examination with finding the erase head. As you can see in the picture below, it is nicely labeled. You can also see that it is indeed physically separated from the play/record head (by about an inch). When recording (or playing), the tape passes over the erase head to be cleared prior to passing over the record head to receive the new audio. As a result, there is always a one-inch section of the tape that will contain no audio at all. This is the gap that I have been hearing in my loops.

|

| The Erase and Play/Record Heads on the Portastudio |

|

| Seeing Where the Erase and Play/Rec Heads are Wired Back to the Main Circuit Board. |

Unplug the Connector: The easiest way to defeat the erase head is, perhaps, simply to unplug it. So, that's what I tried.

|

| To Disable the Erase Head, Just Unplug the Big Connector |

What are the "Erase" Signals: Because I was interested, I hooked up my oscilloscope to the pins on the connector that I just unplugged. I wanted to see what signals where being sent to the erase head. The pictures below show what I found. The connector has 8 pins, and each pair seem to give similar signals (I'd assume that each pair represents a single channel on the 4-track tape). For each pair of pins, one pin showed an 87 kHz signal with an amplitude of ~134 mV RMS. The other pin showed no signal, so it might be ground. I'm assuming that the 87 kHz is the bias signal used by cassette systems as the carrier for real audio signal that is amplitude modulated on that carrier. Since this is the erase head, there should be no audio, so it should just be the 87 kHz signal. This appears to be what I see.

|

| Looking at the Signals on the Connector to the Erase Head. Looks like the 87 kHz AC bias signal (Left) and Ground (Right). |

Trying it Out: So, with the erase head disconnected from the main PCB, I tried recording some audio. As a sound source, I used my Korg Monotron with its funny little ribbon controller. As you heard in the demo tracks tat the top, when I defeat the erase head (by disconnecting it from the main PCB), I successfully eliminate the gap from my looped audio. Fantastic.

|

| Using the Monotron Delay to Create Tracks on the Portastudio |

Visualizing the Results: In addition to listening to the demos, you can see the tracks visually in the spectrograms below. All of the tracks show recordings from the loop tape of the Monotron. The top figure shows a single loop of audio excerpted from a recording when the erase head was connected and active. Note the half-second gap at the end of the loop, which corresponds to that one-inch piece of tape between the erase head and the record head. The middle plot shows the result after I unplug the erase head. Note that the gaps is gone...the loop is continuous. This is what I hoping for.

|

| Spectrograms of the Same Three Audio Demos From the Soundcloud Player at the Top of this Post. |

Layering Audio in One Track: Another important effect of defeating the erase head is that nothing clears the track between recordings. So, when you go to record audio onto a track, it becomes layered on top of the audio that was already there. An example of this sound-on-sound recording is given in the third audio demo (and in the third spectrogram above). Here, I first recorded the basic warbling tone from the Monotron as already seen in my other examples. This is "Layer A". Then, onto the same track, I recorded the Monotron with wilder variations in pitch. This is "Layer B". As is clear in the audio demo and in the spectrogram, both layers are clearly there. Note that this is not a mixture that has been done electronically (ie, read the previous track, mix it with the in-coming new audio, then record the mixed audio onto a fresh track). No, this mixture is being done on the tape itself. As far as I know this is very uncommon.

Imperfect Layering: I believe that one reason why it is uncommon to mix audio onto tape this way is because the layering is far from perfect sounding. Note that as "Layer B" dives from high-pitch to low-pitch (see the blue arrow), it seems to suppress a lot of the "Layer A" sound. It's not until the pitch of "Layer B" raises a bit that the tone from "Layer A" sounds strong again. To most people, this interaction between the two layers of audio would be an undesirable trait. But, not for me...I'm purposely looking for unusual side-effects of using tape. So, to me, this kind of weird artifact is gold!

Have any of you hacked your cassette recorders? What have you done?

Monday, February 10, 2014

Cassette Tape Loop

Over the weekend, after finishing up on my MIDI-to-Trigger converter, I got the idea to dig out my old Tascam Portastudio 4-track cassette recorder (from the early '90s!) and to see what kind of weird noise-hacking fun I could have with the old girl. I had this vision that I could turn it into a monster multi-track tape delay machine with cool sound-on-sound looping. Man, I was getting excited. Before, before diving into modifications of the hardware, I decided to start a little more simply...I decided to start with making a tape loop from a cassette. In the video below, you can see what I did and get a quick demo. I got really lucky and ended up with a sweet saxophone loop. Nice!

I then started trying to make my tape loops. As mentioned later, it took me four tries to get one that worked. The photo below is the configuration that eventually worked...I used both plastic spools. With both spools in place, I cut a segment of tape that was approximately correct in length, including a small amount of overlap...about half an inch (~1 cm) is probably sufficient, though you might want a little more overlap just to make it easier to handle.

Then, I got out my adhesive tape. You want something really thin, so I tried my generic brand and my name brand tapes. For my first two trials (both failures), I used the name brand "Scotch" tape shown on the right. For my third trial (also a failure) and for my fourth trial (a success), I used the store brand. The store brand did seem better in this case...the Scotch brand was "matte finish", which meant it was thicker. No good. Go for the thin (but sticky!) stuff.

Once you've picked the tape that you want to use, you need to cut a *really* small piece. It should be more narrow than the audio tape...and it shouldn't be too long. You can see my piece of tape in the photo below.

Next is the really tricky part. You need to use the little piece of adhesive tape to splice together the ends of the audio tape. While it's OK to have the ends of the audio tape overlap, it is very important that they are align straight. If you don't have a "splicing block" (I don't have one), then this is where you just need to try it and practice. It was really hard at first. Then, I got a system that worked really well for me. You can see the results below.

Now it's ready to be put in your cassette deck and played. If you're like most people, your first bunch of trials won't work. But if you keep trying, you'll get there. As you can see in my video, I had a cool loop already recorded onto my loop tape. Maybe you'll get lucky, too!

If you'd like to make your own cassette loop (for use in a normal cassette deck, or in a fancy 4-track cassette recorder), there are lots of videos and how-to pages on the internet. While I found them helpful, I found that practice was the key. In my photos below, I don't really shed any new light on the matter, but maybe you'll see something that isn't available elsewhere.

First, start with a cassette. I started with an old one of mine that had material already on it. If you're really good, you can purposely excerpt a piece of tape with an audio segment that you're purposely trying to loop. I didn't have such high hopes. I just grabbed a tape that was in the same box as my 4-track cassette recorder. It was a cassette that originally had an Ani DiFranco album (that I recorded from CD probably around 1998). I then re-purposed the cassette to record a jam session at a friend's house (Hi Paula!) in 2000 ("Alpine Music Fest"). Since I have all of that material elsewhere, I decided that this is a good tape to sacrifice for my experiments with making a cassette loop.

Below, you can see the cassette after I opened it up. With it open, I cut the tape and removed the tape from the two white plastic spools.

First, start with a cassette. I started with an old one of mine that had material already on it. If you're really good, you can purposely excerpt a piece of tape with an audio segment that you're purposely trying to loop. I didn't have such high hopes. I just grabbed a tape that was in the same box as my 4-track cassette recorder. It was a cassette that originally had an Ani DiFranco album (that I recorded from CD probably around 1998). I then re-purposed the cassette to record a jam session at a friend's house (Hi Paula!) in 2000 ("Alpine Music Fest"). Since I have all of that material elsewhere, I decided that this is a good tape to sacrifice for my experiments with making a cassette loop.

|

| An old cassette. It once was Ani DiFranco. Then it was re-used to record a jam session. "Alpine Music Fest 2000". |

Below, you can see the cassette after I opened it up. With it open, I cut the tape and removed the tape from the two white plastic spools.

|

| I opened up the cassette to remove the long spools of tape. |

I then started trying to make my tape loops. As mentioned later, it took me four tries to get one that worked. The photo below is the configuration that eventually worked...I used both plastic spools. With both spools in place, I cut a segment of tape that was approximately correct in length, including a small amount of overlap...about half an inch (~1 cm) is probably sufficient, though you might want a little more overlap just to make it easier to handle.

|

| I cut a short segment that would fit once around. |

Then, I got out my adhesive tape. You want something really thin, so I tried my generic brand and my name brand tapes. For my first two trials (both failures), I used the name brand "Scotch" tape shown on the right. For my third trial (also a failure) and for my fourth trial (a success), I used the store brand. The store brand did seem better in this case...the Scotch brand was "matte finish", which meant it was thicker. No good. Go for the thin (but sticky!) stuff.

|

| The cheap clear adhesive tape on the left worked much better than the "fancy" adhesive tape on the right. |

Once you've picked the tape that you want to use, you need to cut a *really* small piece. It should be more narrow than the audio tape...and it shouldn't be too long. You can see my piece of tape in the photo below.

|

| I then cut the smallest piece of adhesive tape ever. |

Next is the really tricky part. You need to use the little piece of adhesive tape to splice together the ends of the audio tape. While it's OK to have the ends of the audio tape overlap, it is very important that they are align straight. If you don't have a "splicing block" (I don't have one), then this is where you just need to try it and practice. It was really hard at first. Then, I got a system that worked really well for me. You can see the results below.

|

| I used the little piece of adhesive tape to splice the audio tape it into a single loop. It ended up being about 5 seconds long. |

The only thing wrong with the photo above is that the tape is too tight. When it didn't work (at first), I tried loosening the tape a little bit. How? Well, if you look closely down by each one of the little white rollers, you'll see that the tape goes around a thin dark-plastic post. To make my tape loop a little looser, I pulled up the tape and allowed it to NOT pass around one of those posts. This was just the amount of slack that it needed. It worked! Yay!

To finish the loop, you can use your scissors to trim away any audio tape that overlaps at the splice. You don't need to get it perfect, but it is good to minimize the overlapping tape. Then, put the cover back on the cassette and screw it back together. Oh, and then rename the cassette. In my case, this is its third name!

|

| Here's the re-assembled cassette. Ani DiFranco and the Alpine Music Fest have now become a loop tape! |

Now it's ready to be put in your cassette deck and played. If you're like most people, your first bunch of trials won't work. But if you keep trying, you'll get there. As you can see in my video, I had a cool loop already recorded onto my loop tape. Maybe you'll get lucky, too!

My next steps are to record some droning sounds on the four different tracks so that I can dynamically mix them together in a moody way. I'm thinking that it will sorta be like my Kaossilator Pro (which is built to have four independent loops)...except the tape-based loop will be dirty sounding and not clean like the Kaossilator. Hopefully, it'll be dirty in a good way.

After that, my plan is to see if I can defeat the erase head on the Portastudio so that I can attempt sound-on-sound layered recording. Again, it'll be like the Kaossilator (which does sound-on-sound) except the Portastudio can add all of the sound mangling artifacts that come with audio cassettes. Here I'm particularly interested in what happens when you overload the tape (ie, write on it many times without erasing) and what happens when you bounce back and forth between tracks so many times that the generational losses become dominant. This could be seriously fun!

Sunday, February 9, 2014

Arpeggiator Fun -- Dual Arps and MIDI Sync

In my previous post, I described how I made an Arduino-based MIDI-to-Trigger converter so that I could combine my love of old-school arpeggiators with newer MIDI-equipped drum machines. I gave a video demo of me driving the arpeggiator of my Korg Mono/Poly using the MIDI Clock output from my Korg Kaossilator. In this post, I take it one step further. Today, I'm going for gold...I'm going to drive two arpeggiators at the same time. Twice the fun!

As shown above, the setup is pretty straight-forward. The Kaossilator is providing a MIDI clock signal. I connect it's MIDI Out to the MIDI in on my homemade trigger converter. My converter has two trigger outputs. I connect one trigger output to the "Arp Trig In" jack on the Mono/Poly and the other trigger output to the similar jack on the Polysix.

Below is a demo using this setup. It is a single-take where all instruments are playing live without any sequencing or anything from the computer. It's just the arpeggiators from the two synths and the Kaossilator.

A key feature of the track above is that I set the arpeggiators to play at different rates. I did this using the potentiometer knobs on my MIDI-to-Trigger converter. The effect is apparent right at the beginning of the track where the Polysix is playing one note every four beats whereas the Mono/Poly is rippling out eighth notes. The Kaossilator is providing the drums. Without my MIDI-to-Trigger converter, it would not have been possible to keep the drums in sync with the two arpeggiating synthesizers. It's much more fun this way.

For a second demo of this setup, the track below is also a live-recording of the Polysix plus Mono/Poly plus Kaossilator. In this track, though, the kick drum and snare sounds are actually being produced by the Mono/Poly (it's a very flexible synth). The arpeggiating synth is the Polysix. Everything else (hi-hats, bass sounds, leads) are all from the Kaossilator.

So, that's the fun that I've been having hooking everything together. Sure, by modern standards of EDM, this might not be too exciting...but I could play with these kinds of sounds for hours. I just love the sound of it all.

Use the comment section below and share with me your own joys with arpeggiators!

|

| I'm Using Trigger Outputs for Dual Arpeggiator Glory! |

Below is a demo using this setup. It is a single-take where all instruments are playing live without any sequencing or anything from the computer. It's just the arpeggiators from the two synths and the Kaossilator.

A key feature of the track above is that I set the arpeggiators to play at different rates. I did this using the potentiometer knobs on my MIDI-to-Trigger converter. The effect is apparent right at the beginning of the track where the Polysix is playing one note every four beats whereas the Mono/Poly is rippling out eighth notes. The Kaossilator is providing the drums. Without my MIDI-to-Trigger converter, it would not have been possible to keep the drums in sync with the two arpeggiating synthesizers. It's much more fun this way.

For a second demo of this setup, the track below is also a live-recording of the Polysix plus Mono/Poly plus Kaossilator. In this track, though, the kick drum and snare sounds are actually being produced by the Mono/Poly (it's a very flexible synth). The arpeggiating synth is the Polysix. Everything else (hi-hats, bass sounds, leads) are all from the Kaossilator.

So, that's the fun that I've been having hooking everything together. Sure, by modern standards of EDM, this might not be too exciting...but I could play with these kinds of sounds for hours. I just love the sound of it all.

Use the comment section below and share with me your own joys with arpeggiators!

Labels:

Arduino,

Arpeggiator,

Audio,

Kaossilator,

Korg,

MIDI,

Mono/Poly,

Polysix

Arpeggiator Fun -- My MIDI-to-Trigger Converter

I'm going to admit it...I love arpeggiators. I love their inhumanly-perfect, never-ending rippling waves of beautifully-synthetic tones. It's so hypnotizing to me. What I like even better is if I add a drum machine to play along with the arpeggiator. But how do you keep the two devices in sync with each other? In a previous post, I showed how I used the "trigger out" of my old TR-707 drum machine to drive the arpeggiator on my Korg Polysix. While that worked fine, my newer drum machines don't have trigger outputs. Instead, they output MIDI. Since my synths don't talk MIDI, today's post shows how I built a MIDI-to-Trigger converter using an Arduino. The video below is a quick demo...

What Does the Converter Do? I have two old synths -- a Korg Mono/Poly and a Korg Polysix. Both of these synths have a built-in arpeggiator and both synths have a jack on the back for "Arpeggio Trig In". If you send a voltage pulse into this jack, it will cause the arpeggiator to step to the next note. As a result, you can keep the arpeggiator in sync with old drum machines that have trigger outputs (such as my old TR-707). My Korg Kaossilator, however, is much newer and it does not output trigger signals. Instead, it sends out a MIDI clock signal. My synths are too old for MIDI. So, if I want to keep my Kaossilator in sync with my Mono/Poly or my Polysix, I need a device to listen to the MIDI messages and to issue trigger pulses at the right times. That's what my MIDI-to-Trigger converter does.

The Shopping List: The heart of my MIDI-to-Trigger converter is an Arduino Uno ($30). To enable it to receive MIDI messages, I used a Sparkfun MIDI Shield ($20) that has the female MIDI connectors and the associated electronics to get the MIDI messages into the Arduino. Helpfully, the MIDI shield also includes two potentiometers and three push buttons. Very nice! To physically connect the MIDI shield to the Arduino, I also had to buy some stackable headers ($1.50). Finally, to get the trigger signals out of the Arduino and headed towards my synth, I chose to buy some 1/8" stereo audio jacks ($1 each), though any jacks will do (1/8" or 1/4" or whatever). I chose to include two audio jacks so that I can drive two arpeggiators at the same time (ie, both my Mono/Poly and my Polysix) because, if one arpeggiator is good, two must be even better!

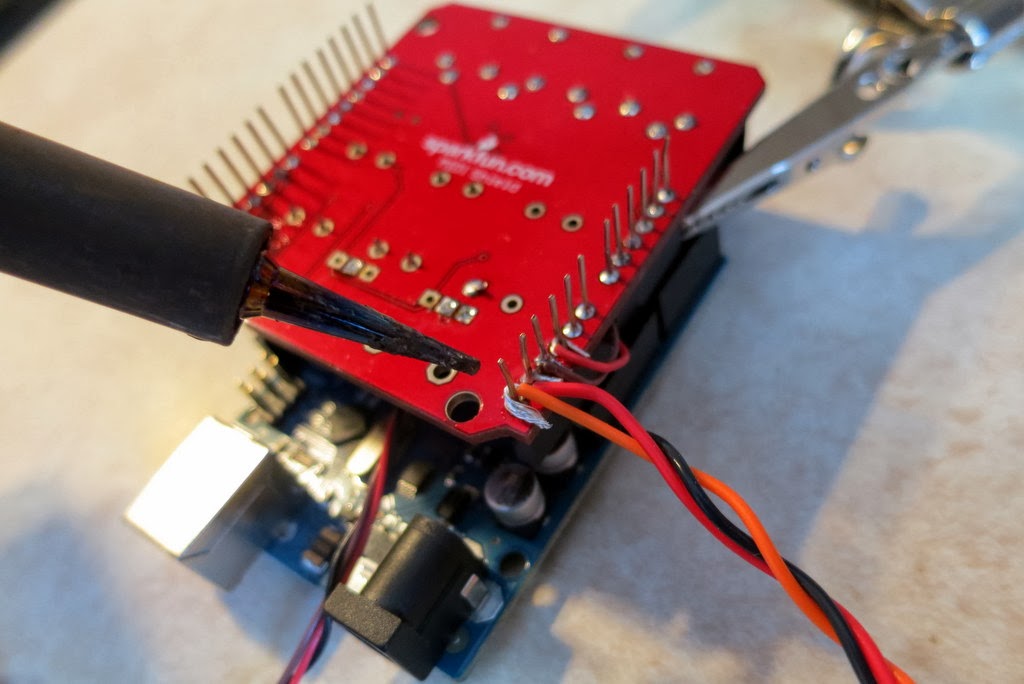

Assembling the Hardware: The MIDI shield comes as a kit that you need to solder together yourself, which is pretty direct and easy. After the shield was assembled, I then needed to attach my two audio jacks to convey the trigger signals out to my synths. Unfortunately, there are no solder holes on the Arduino or on the MIDI shield for attaching jacks or wires. So, I chose to solder some wires to the pins that connect the MIDI shield to the Arduino. Usually, this is not recommended approach, and you should be aware that it is a bit challenging to do (notice the tight space in the picture below) but it did work for me.

Once the wires are attached to the MIDI shield, then you just have to attach the jacks to the other end of the wires. As shown in the picture below, soldering to the jacks is much easier.

Finally, once all of the soldering is done, you simply mate the MIDI shield to the Arduino. The hardware is done!

Writing the Basic Software: For the Arduino, I wrote some software that listens for the messages coming in from the MIDI port. MIDI is quite general (it's not just about keeping time) so my Arduino is programmed to ignore most of the traffic on the MIDI bus. It is listening solely for MIDI Beat Clock messages (ie, code 0xF8). The MIDI standard says that there should be 24 of these messages arriving for every quarter note. So, if I want a 16th note arpeggiation, and since a 16th note is a 1/4 of a quarter note, I programmed the Arduino to issue a trigger pulse after every 6 MIDI clock messages (because 24 * 1/4 = 6). To actually issue a "trigger pulse", the Arduino briefly raises (or lowers) one of its digital output pins. That's the trigger signal. That's all it takes!

Adding Fancy Features: Once I had the basic software working, I started adding features. First, because some arpeggiators like upward-pulses and other like downward-pulses, I wrote the software to do both. That's why I use stereo jacks for my outputs...the "left" channel is upward going while the "right" is downward going. The next feature that I added is a second set of trigger outputs to drive a second arpeggiator (hence my inclusion of the second audio jack). Then, to be adjust the speed of the arpeggiators relative to the MIDI clock (do I want 16th notes? 8th notes? whole notes?), I program the Arduino to read the two potentiometers and to set the MIDI clock divider (that number "6" discussed in the paragraph above) to make the triggers come faster or slower. This is pretty sweet.

Sharing My Software: I case anyone is interested, you can get the latest version of my MIDI-to-Trigger Arduino software at my GitHub, which is here. If you make improvements, send me a pull request!

Trying it Out: So, for my initial trials, I kept the setup simple. My Korg Kaossilator is going to be my drum machine. I'm going to have it drive the arpeggiator on my Mono/Poly. So, as shown in the figure below, I connected the Kaossilator's "MIDI Out" to the "MIDI In" on the Arduino MIDI-to-Trigger Converter. Then, I connected a cable from one of my converter's outputs to the "Arpeggiator Trig In" jack on the back of my Mono/Poly.

Once it was all connected together, I started some drum loops on the Kaossilator. Then I activated the arpeggiator on the Mono/Poly, I set it to "Latch", and then I locked in a few notes. And then nothing happened. After chasing down a couple of bugs in my software, I tried again. And then again. And eventually, I got it to work. The arpeggiator was stepping in sync with the Kaossilator. It was glorious. As shown in the video at the top of this post, I can change tempo and it all keeps going in sync. It's pretty fun.

Follow-Up: Two arpeggiators at the same time!

The Shopping List: The heart of my MIDI-to-Trigger converter is an Arduino Uno ($30). To enable it to receive MIDI messages, I used a Sparkfun MIDI Shield ($20) that has the female MIDI connectors and the associated electronics to get the MIDI messages into the Arduino. Helpfully, the MIDI shield also includes two potentiometers and three push buttons. Very nice! To physically connect the MIDI shield to the Arduino, I also had to buy some stackable headers ($1.50). Finally, to get the trigger signals out of the Arduino and headed towards my synth, I chose to buy some 1/8" stereo audio jacks ($1 each), though any jacks will do (1/8" or 1/4" or whatever). I chose to include two audio jacks so that I can drive two arpeggiators at the same time (ie, both my Mono/Poly and my Polysix) because, if one arpeggiator is good, two must be even better!

|

| The components in my MIDI Clock to CV Trigger Converter. |

Assembling the Hardware: The MIDI shield comes as a kit that you need to solder together yourself, which is pretty direct and easy. After the shield was assembled, I then needed to attach my two audio jacks to convey the trigger signals out to my synths. Unfortunately, there are no solder holes on the Arduino or on the MIDI shield for attaching jacks or wires. So, I chose to solder some wires to the pins that connect the MIDI shield to the Arduino. Usually, this is not recommended approach, and you should be aware that it is a bit challenging to do (notice the tight space in the picture below) but it did work for me.

|

| A kludge. I'm soldering the wires to my audio jack to the pins on the MIDI Shield that will mate to the Arduino. Generally, this is not recommended, but it works. |

Once the wires are attached to the MIDI shield, then you just have to attach the jacks to the other end of the wires. As shown in the picture below, soldering to the jacks is much easier.

|

| Soldering the wires onto the audio jack. These don't carry audio. They carry the CV Trigger signals. |

Finally, once all of the soldering is done, you simply mate the MIDI shield to the Arduino. The hardware is done!

|

| My fully-assembled device for converting MIDI Clock to CV Triggers. |

Writing the Basic Software: For the Arduino, I wrote some software that listens for the messages coming in from the MIDI port. MIDI is quite general (it's not just about keeping time) so my Arduino is programmed to ignore most of the traffic on the MIDI bus. It is listening solely for MIDI Beat Clock messages (ie, code 0xF8). The MIDI standard says that there should be 24 of these messages arriving for every quarter note. So, if I want a 16th note arpeggiation, and since a 16th note is a 1/4 of a quarter note, I programmed the Arduino to issue a trigger pulse after every 6 MIDI clock messages (because 24 * 1/4 = 6). To actually issue a "trigger pulse", the Arduino briefly raises (or lowers) one of its digital output pins. That's the trigger signal. That's all it takes!

Adding Fancy Features: Once I had the basic software working, I started adding features. First, because some arpeggiators like upward-pulses and other like downward-pulses, I wrote the software to do both. That's why I use stereo jacks for my outputs...the "left" channel is upward going while the "right" is downward going. The next feature that I added is a second set of trigger outputs to drive a second arpeggiator (hence my inclusion of the second audio jack). Then, to be adjust the speed of the arpeggiators relative to the MIDI clock (do I want 16th notes? 8th notes? whole notes?), I program the Arduino to read the two potentiometers and to set the MIDI clock divider (that number "6" discussed in the paragraph above) to make the triggers come faster or slower. This is pretty sweet.

Sharing My Software: I case anyone is interested, you can get the latest version of my MIDI-to-Trigger Arduino software at my GitHub, which is here. If you make improvements, send me a pull request!

Trying it Out: So, for my initial trials, I kept the setup simple. My Korg Kaossilator is going to be my drum machine. I'm going to have it drive the arpeggiator on my Mono/Poly. So, as shown in the figure below, I connected the Kaossilator's "MIDI Out" to the "MIDI In" on the Arduino MIDI-to-Trigger Converter. Then, I connected a cable from one of my converter's outputs to the "Arpeggiator Trig In" jack on the back of my Mono/Poly.

You can see the connections to my MIDI-to-Trigger converter in the photo below.

As seen in the picture below, with all of these extra wires running around, the setup gets a little messy.

|

| Zooming out to see the whole setup. Wires everywhere! |

Once it was all connected together, I started some drum loops on the Kaossilator. Then I activated the arpeggiator on the Mono/Poly, I set it to "Latch", and then I locked in a few notes. And then nothing happened. After chasing down a couple of bugs in my software, I tried again. And then again. And eventually, I got it to work. The arpeggiator was stepping in sync with the Kaossilator. It was glorious. As shown in the video at the top of this post, I can change tempo and it all keeps going in sync. It's pretty fun.

Next Steps: The next steps are to run the arpeggiator on my Mono/Poly and the one on my Polysix at the same time. That'll be a really fun. Look for a follow-on post!

Follow-Up: Two arpeggiators at the same time!

Labels:

Arduino,

Arpeggiator,

GitHub,

Kaossilator,

Korg,

MIDI,

Mono/Poly,

Video

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)